David R. Kotok's Remarks at the Rocky Mountain Economic Summit, Thursday, July 15

Note: This is the formal presentation; actual remarks may stray from the text or be abbreviated for the sake of time.

Thank you very much, Justin Hyde. It's a pleasure to be here. I've been absent for the last three years, and I want to tell you and everyone in this room how good it feels to be back here.

I'm a believer in history. Famous words by the Spanish poet George Santayana translate into something like this: “Those who cannot remember their history are condemned to repeat it.” I'm not sure condemned is the right word when it comes to this salubrious gathering. But it may be the right word when we fail to heed lessons from pandemics, and I'll get to that subject in a minute or two.

Let me just share a little history here. The first Rocky Mountain Summit was really an entrepreneurial gathering in Afton, Wyoming, that Justin and Cody Hyde and others convened; and it was held in the Afton Community Center. I didn't attend, by the way, but I had lunch with Justin in Salt Lake City a few months after that and proposed that the Global Interdependence Center and the Bronze Buffalo Club, which was in its early stage, partner to do this event together, and Justin agreed. Justin, if I remember correctly, we had lunch at the Market Street Grill in downtown Salt Lake, but I might be wrong, because we've had a few lunches along the way.

The second Rocky Mountain Summit again took place in the Afton, Wyoming, Community Center. My friend John Silvia, whom you've just heard, joined me. St. Louis Fed President Bill Poole, our mutual friend and now a fellow at the Global Interdependence Center College of Central Bankers, had just retired, and he joined us. So Bill, John, and I became the program with introduction by Justin at Rocky Mountain Summit 2.

And I guess it was successful enough that the people who came wanted more, and others who heard about it said, “Let's do it again.” So I said, “Justin, why don't we move this to Jackson Hole?” And he agreed.

We then moved from the Afton Community Center to the Center for the Arts in downtown Jackson Hole, and that became the third and the fourth Rocky Mountain Summit and on and on, and here we are now at one of the signature economic conferences, policy conferences, entrepreneurial conferences that the Global Interdependence Center orchestrates. It hosts many all over the world. This great partnership between the Bronze Buffalo Club, of which I am a member, and the Global Interdependence Center is now celebrating year thirteen.

So, Justin, there's a piece of history that we are happy, not condemned, to repeat. We remember it with affection and respect, and we're glad to be back here. The last three years I had to miss. I asked Ed Schulak, my partner in this session, if he would cover for me at the Trout Ranch fishing tournament, and he promised me that he would protect my honor and his. I hope, Ed, that you were able to catch the trophy albino trout. I think it's in the seventh pond station, but that's from memory, so I don't know where the fish are because I haven't been for a couple of years.

For me, this has been a somewhat difficult time because I've had to confront a few issues in addition to a pandemic, but to quote the great American author Mark Twain, "Rumors of my demise are greatly exaggerated." So thanks for inviting me back, and it's nice to be here with all of my GIC colleagues and Speaker Ryan and many good friends.

Ed and I have spoken in advance of this session, and we’ve decided that the best approach is to divide our time. So let me go to work at once.

First we have a short video from YouTube, and I'm introducing it with two things in mind. Number one, it will convey a sense of the ongoing global pandemic. Number two, I want to add that the source of this video is the English-language edition of the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. The video is also available in the Chinese edition, in a country where the government determines what 1.4 billion people can read and see in the news. Let's run the video.

Source: “China ‘cannot relax coronavirus controls’ amid threat from Delta variant,” https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3140547/china-cannot-relax-pandemic-controls-amid-threat-delta-variant

With the sobering reality of the ongoing global pandemic in mind, let’s move on.

(Black swan photo by David Kotok taken at Japanese temple on Oahu, Hawaii.)

Many people in the financial markets and the economic community call COVID a black swan. Author and former options trader Nassim Taleb has, with mathematical precision, defined a black swan. What he really said was, "This is a surprise. It's a rare, unpredictable event. There's no preparedness for it. There's not a lot of warning.”

I would like to, in the next eight minutes or so, disabuse this audience of the notion that COVID is a black swan. Let’s look at the evidence.

(Source: “Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics,” https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/wp2020-09.pdf)

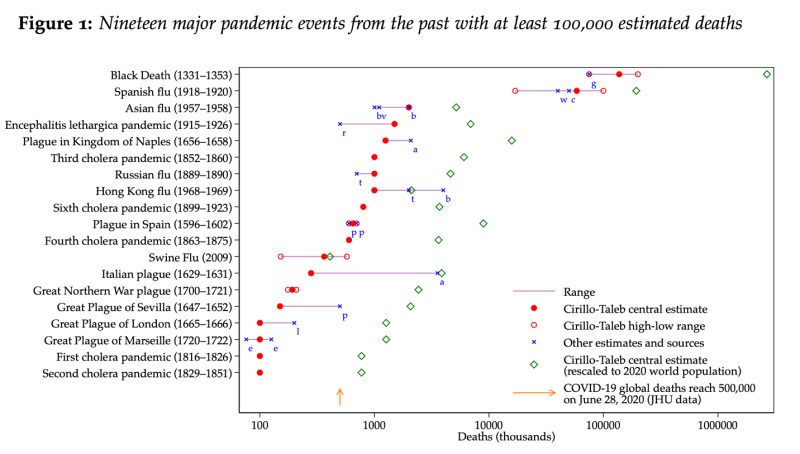

The slide lists the 19 pandemics over the last 700 years that had an adjusted death estimate of over 100,000 people. It comes from a study put together at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Notice, by the way, that Ebola is not on the list. It wasn't big enough. These are the 19 big ones.

At the top of the list, you see the Black Death in Europe, which occurred about seven centuries ago — it killed a third of the world's population, roughly. How we estimate these things from 700 years ago is a separate question, but anybody can check out the math if they want to.

Notice that the Spanish flu is number two. That's the 1918 reference we all use and that has really dominated our thinking because of John Barry's famous book The Great Influenza and others. Barry’s book is worth reading — I've read it — but it's also worthwhile, if you have the time, to explore all the additional information that would complete the picture of what was really the 1917–1921 period, with mutations and repeated outbreaks of the 1918 Spanish flu.

Today, I'm going to get to another pandemic as a useful historical analogy for COVID, and that's the 1957–58 Asian flu. If you'll notice, it also makes the list of the big 19, and there are additional lessons to learn from it.

Niall Ferguson, in chapter 7 of his wonderful new book Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe, has done a deep study of 1957 and 1958. Niall is a scrupulous researcher and an incisive historian whose riveting work encompasses both economics and history. Having read several of his books, I cannot praise his work highly enough. But what did he discover? He mapped an instructive historical analogy for COVID, and it's not 1918. It's 1957–1958. By the way, I was a teenager. I'm not sure I remember the Asian flu, but I do remember kids getting sick, parents worrying about the flu, people doing things. Now what makes 1957–58 so important? Why does Niall choose it as the metaphor to examine and learn from? There is a reason.

There was only one president of the United States who in his professional career faced two pandemics. His name was Dwight Eisenhower. Dwight Eisenhower, as a younger officer, had to deal with the 1918 Spanish flu. What did he do? He empowered medical professionals to handle treatment and the science. Remember, this is 1918 — a hundred years ago.

He listened to their advice regarding highly transmissible respiratory illness. He had 10,000 men under his command at the time, at Fort Colt, and what did he do? He put them all in tents. He separated them. There were no more than three together at any given time. Dwight Eisenhower, as a military officer, adopted social distancing in 1918. His experience and his study of disease allowed him to think in terms —military terms — that disease can decimate armies.

Now, fast forward to the 1940s, when the United States, at war, realized that there was a risk of biological weapons. In 1950, we worried about that risk during the Korean War. Look where Eisenhower was during all this time. Think about him and his history and his experience. He became president of the United States after World War II.

At Walter Reed Medical Center in those days, Maurice Hilleman headed the epidemiological activity of the United States Army. The Defense Department was concentrated at Walter Reed, where Hilleman was researching and developing vaccines. He had a full staff. He developed a number of vaccines we still use today.

Vaccines and other mitigations have been in existence in the United States for over half a century. Don't listen to those who would tell you otherwise. Pandemics are not new. Vaccines are not new. Preparation and implementation are not new. What is new? Well, we're going to get to that in about three minutes.

Dr. Hilleman followed outbreaks and symptoms and mutations all over the world, and when he noticed a report of glassy-eyed children in Hong Kong, he said, there's a mutation taking place in the flu virus. That's what would cause that. He had virus samples by May 13 of 1957. By May 22, his staff had taken apart the genetic composition of that virus. They launched vaccine preparation. Six companies in the United States jumped into the task. The leader was Merck. Vaccines were developed within a matter of weeks. The military started inoculations just over three months later.

In 1957–58, as president, Eisenhower inoculated the entire military of the United States. You didn't have a choice. You were a recruit; you got a shot in the arm. That shot kept you alive, by the way. What did Eisenhower do? In a matter of months, he accomplished the vaccination of 17% of the US population.

Companies ramped up production. There was no lockdown. The total public health budget was, according to the research that Niall Ferguson did, $2.5 million. Million with an M, not B for billion. That was the Eisenhower method — protect the military in case there's a military event. Think of the late 1950s. We had the Cold War. We'd just finished the Korean War. We'd just ended World War II.

So what happened in the general population? There was some vaccination. There was also resistance to vaccination. There has always been resistance to vaccination ever since Jonas Salk created the polio vaccine and since the first smallpox vaccine existed. And the result of resistance to vaccination has always been more death and more disease. Every single time. No exceptions.

Now, what else happened? Back in 1918 we didn't have medical treatments; we didn't have ways to deal with the outcomes of getting sick, other than to try to keep people comfortable, hoping they would live. But by 1957–1958, we had medicines. We could deal with some side effects. And now we can do a lot more, although COVID still claims far too many lives.

So you look at the lessons, and what do you see? You see that social distancing prevented disease, and vaccination prevented death. Nothing has changed.

You also see that a pandemic was, for Eisenhower, not technically a black swan. Pandemics are black swans only if you forget your history and the lessons you can apply. When you forget all that, you lose your way, and you intensify the shock that a pandemic delivers.

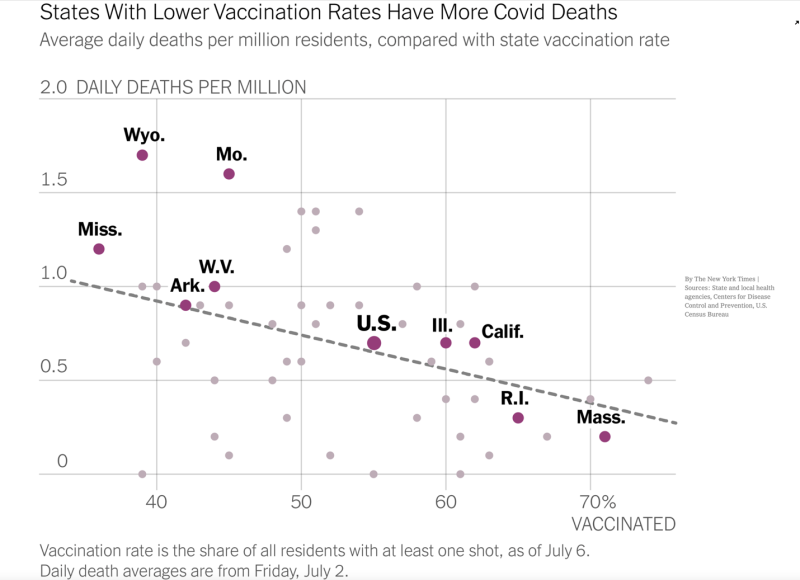

Let’s look at the US today. We're in Wyoming. Here's a slide from July 7, published in the New York Times, that captures data for some key states — specifically, the rates of vaccination, and the rates of death per million people.

(Source: “More Red-State Trouble,” https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/07/briefing/delta-variant-spread-red-states-us.html)

Per capita numbers are very important here. Notice the position, in the upper left-hand quadrant, of Wyoming. Many people in this room are from Wyoming. The state has the lowest vaccination rates, the highest per capita death rates as of July 7. The facts speak for themselves. I didn't make these numbers up; they are based on state, local, and CDC data.

Let's move on to what the US and the world are facing. Our time is limited, but let me strongly recommend that you listen to Episode 60 of a podcast by Mike Osterholm, the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, or CIDRAP, at the University of Minnesota. Osterholm is one of the preeminent epidemiologists in the world, and the podcast is free.

Osterholm Update: COVID-19 Episode 60: “A Formidable Foe” July 8, 2021

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/COVID-19/podcasts-webinars/episode-60

This podcast brings you current about the Delta variant and the situation in the United States. Osterholm makes it a point to be nonpolitical. He's a public health servant above all. I invite you at your leisure to listen to the podcast.

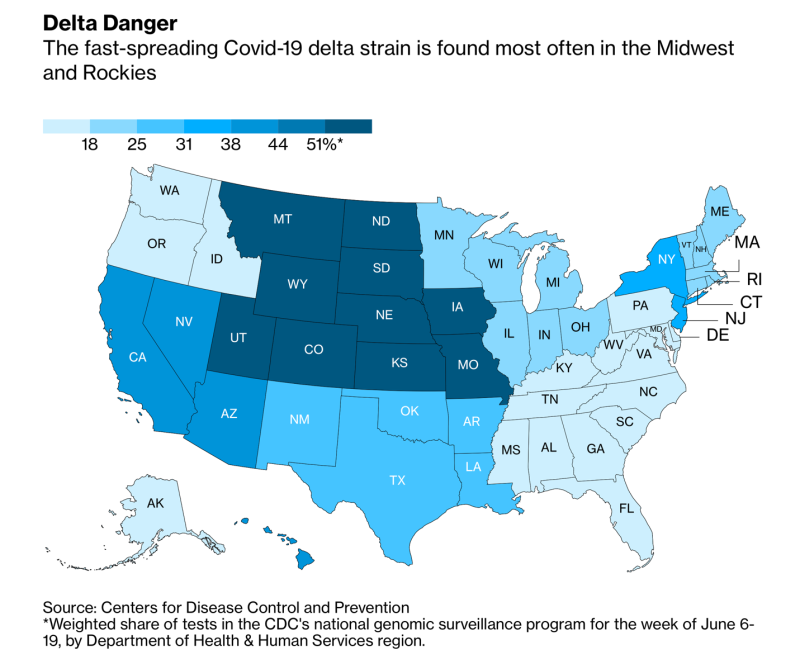

(Source: “Trump Country Rejects Vaccines Despite Growing Delta Threat,”

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-07-07/where-is-delta-spreading-u-s-midwest-rockies-as-trump-country-rejects-vaccine)

Our next chart is from Bloomberg. It shows the distribution of the Delta variant in the United States; and, of course, if you look at the division of the politics of the United States, you see a lot of it, unfortunately, reflected in where fast-spreading COVID-19 infections caused by the Delta variant are gaining momentum. You see that in the Midwest, in the Rockies, and in the South mostly. The chart speaks for itself, and it will evolve rapidly in weeks to come. The data sources are in the chart.

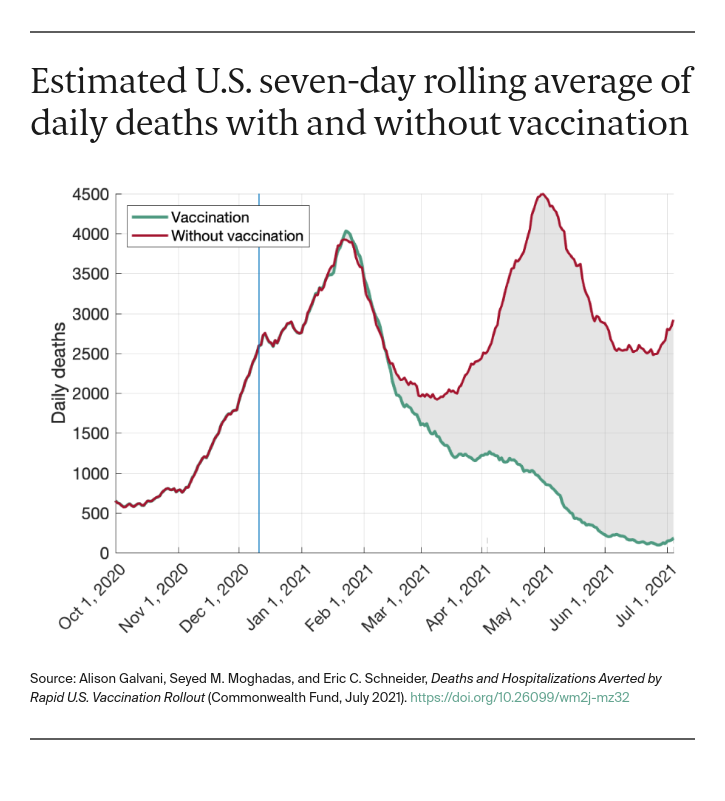

(“Deaths and Hospitalizations Averted by Rapid U.S. Vaccination Rollout,” https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2021/jul/deaths-and-hospitalizations-averted-rapid-us-vaccination-rollout)

The last vaccine/disease chart is this one. It's the construction of a counterfactual calculated by mathematicians and made available by Commonwealth Fund. Essentially what the authors said is that this is what the death rate would have been if we hadn't vaccinated as we have done to date. The data they used for this estimate is the kind of data that you are able to obtain from other large pandemics like '57–'58 or the Spanish flu or others. Now, the model is a counterfactual. We did vaccinate. As a result, we’ve had many fewer deaths in the United States this year than we would have suffered otherwise; it's as simple as that. The mathematical comparison can give you guidance.

Unfortunately, we are still under-vaccinated in the United States even though we have such marvelous resources. We have a thousand counties where vaccination rates are under half — 25%, 30%, 35% — and those rates aren’t moving much. Meanwhile, we have the Delta variant exploding. We know Delta poses a risk to somebody like me, even with two shots of Moderna and all the other defense that I do.

If you had COVID and you had Alpha, you can get Delta, and it can make you sick. That's Delta. And we don't know enough yet about Gamma, and we certainly don't know enough about Lambda, which is decimating Peru as we speak. We do have early evidence that Lambda is both highly contagious and more capable of immune escape than other key variants of concern are.

But now let’s get to the other side of this conference, the economic and financial implications and the outlook. You saw the list of the nineteen pandemics. What do we know in economic terms? Every single one of those events coincided with or was followed by a recession. When you have a natural disaster — a hurricane, a fire, an earthquake, a tornado — it destroys capital stock — the buildings, the levee. You set about to rebuild the buildings. You don't want the damage. Nobody wants a hurricane. Nobody wants to lose capital stock investments, but that’s the kind of damage most natural disasters do. The earthquake shakes the buildings, they fall down, and then we go about the next few years rebuilding and fixing them.

When you have a pandemic, you lose people, not buildings. If you count the official statistics in the United States, somewhere over 600,000 people are dead because of COVID. If you go to the University of Washington’s site for the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), they have the best estimates, I believe, of excess deaths; and excess deaths is the key number.

What they have done is add back positives, for example, lower flu deaths because we had people wearing masks. So they've netted out the numbers to obtain a COVID shock number. As of early May, the United States was approaching one million excess deaths attributable to the COVID shock. The number is still getting larger. Average life expectancy in the United States has declined by two years, for the first time in modern American history.

Think about the impact of the decline in life expectancy, and, lastly, think about the fact that in the United States the population growth rate actually shrank during the pandemic. There are fewer of us here than we thought there would be today. Well, you might say that part of that decrease in population growth was driven by immigration policy, and part of it by the Trump administration's making it more difficult for people to get into the country. And you know what, some of that is true. But part of it was also COVID. The combination means this: In the United States today, life expectancy is down two years, and the population growth rate is almost flat.

Imagine the economic shock if you're in the insurance business. If you were planning any business model, any entrepreneurial model, up through 2019, you based your calculations on the demographics of the United States: You knew there were almost 330 million of us; you knew how old we were, our gender; you knew our composition; you knew it racially; you knew it ethnically; you knew language.

But now, all of a sudden, you’ve had a shock. And all the estimates you did for long-term economics are now shattered. Ask any actuary you know, for any insurance company, if you don't want to take my word for it.

Let's move on to the next issue. What we now know, from all the information available, is that somewhere between 10% and 30% of people who have survived COVID have developed a range of lingering symptoms we call long haul COVID, or post-COVID syndrome. Those symptoms may be neurological, and they may be cardiac, and they may be respiratory, but long haul COVID is a brand-new thing. It didn't exist a year ago. There are 33 clinics now in the United States devoted to learning about and treating long haul COVID. There wasn't one a year ago. The estimates are that there will be hundreds of long haul COVID clinics by the time this pandemic runs its course.

The number of people contending with long haul COVID symptoms is in the millions and growing all the time. You can get COVID today, and it's mild. You say, “Ah well, it wasn't so bad, you know. It was like a bad cold; it was like a big flu.”

And guess what? In the weeks and months that follow, you develop new symptoms; a year from now, you get a scan, and you find scarring that happened in your brain or in your lungs. Or you have a circulatory issue, and you go to your cardiologist, and your cardiologist asks, “Gee, did you have COVID? When did you have it? What was it like?” How do we get from the COVID you had last year to the cardiology problem this year? We're all learning about what COVID does as we go. This is new.

There are now millions of long-haul-COVID victims in the United States, and the number is growing every day. A Long COVID Alliance has formed. I'm involved with it. There are professionals in various disciplines of medical science and biology focused on it, and the number of COVID long haulers of all ages is growing every day. The Global Interdependence Center hopes to sponsor in New York in December a worldwide meeting on this subject.

Now, why am I banging the table up here in Teton Springs about long haul COVID? Here's why. Here's the economic issue. Long haul COVID victims are disabled. They are either partially disabled or fully disabled. We don't know for how long. But we now see in some cases a year of disability and counting. We haven't had COVID around long enough to know what happens 5 or 10 years down the road. We’re only just starting down a track that will involve millions and millions of people in the United States.

Now think about what I just said. If you have a shock, and the shock impacts people, not buildings, what happens economically? You don't need to rebuild the buildings. You don't need to borrow all the money. You don't need to have all the financial leverage to construct. Your shock is people-oriented instead.

The economic trajectory charted early last year was supposed to take us to 155 million American jobs right now, from the 153 million counted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in February of 2020, the last pre-COVID month. We had 153 million then, 155 million projected to be the case now, and where are we? We're 10 million jobs short.

And we can watch wages rise — wages rose after every pandemic. The histories of those 19 pandemics can back me up. The price of labor went up. The number of people to fill positions went down. Something else happened in the financial world: Real interest rates went down, because the demand for capital was not to rebuild the buildings.

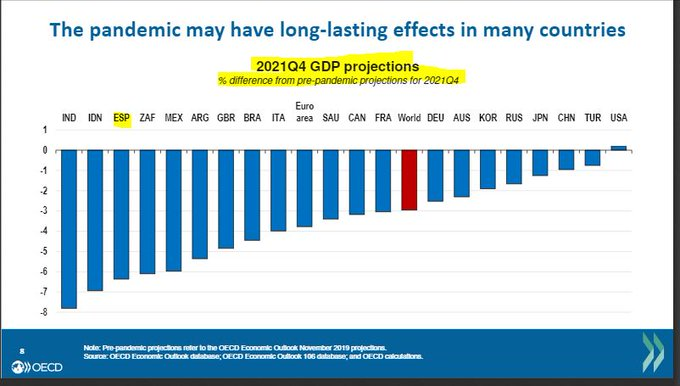

This latest estimate from the OECD shows how big the COVID global shock may become. Folks, pandemic means worldwide. This one is huge. And nearly 7 billion people on this planet do not yet have the benefit of a single shot of any vaccine.

“Source: OECD"

Think about it. The entire thought process that you've been talking about all day here, concerning the Federal Reserve, and debt, and interest rates, and markets and financial markets, is upside down. COVID is a profound shock. We don't know precisely how big it will be. We don't know how long it will go on. It is not business as usual, and it's not over — not even close.

In every pandemic and in every major shock there are financial winners and losers. Those who see it for a shock and those who, as George Santayana said, remember their history can apply the metrics of their trade. They will benefit. Sadly, they will benefit because of the disease and death of others. That's a tragic tug-of-war. For me, as a money manager, as a financial market agent, I struggle. And with the Global Interdependence Center, I put on a hat that says, "Worry about the policy issues."

But as an old money manager with 50 years in business, I say we have to react to what we have and apply the tools. There are pandemic strategies, tools you use to deal with shocks. For example, in our history at Cumberland, on a second cluster of cases, we change market positions. On the first trigger, we go to warning status — anywhere in the world, any disease, any time. Sometimes you do it, and nothing happens, and then you change.

I want to add a personal note, and then I'm going to stop. By luck of the draw, I have followed infectious disease since 1966. There was no plan, no grand design, to do this. But in 1966 I was a second lieutenant in the United States Army. My family has a history of being involved in serving the country. My father was in the Navy in World War II. I had a great uncle who rode cavalry under General Pershing. I had a cousin who spent the Korean War in the Air Force in Korea. Military service is a tradition in my family.

My first assignment was the 486th Preventive Medicine Unit, which was the unit attached to the 7th Army Europe, and its purpose was to prevent soldiers from getting sick from disease and infections. And it was the craziest military unit you ever saw. I was the detachment commander, and our job was to keep the epidemiologists and entomologists and all the other –ologists safe while they went in jeeps with specialists to do all kinds of things with bugs of all types.

My boss was a major, and he remembered World War II; and his boss, a two-star general, a wonderful man, knew Eisenhower. This was 1966. The 1950s and World War II weren’t very far back for these folks. They were for me, but they weren't for them. And I remember the lesson they taught me. If you're going know something military, learn about disease. Disease kills more people in military conflicts than guns and tanks do. So I started in 1966, and I've been actively chasing bugs of all types ever since.

I'm going to end with this note. We are a challenged population in 2021. We are not behaving well. Niall Ferguson will tell you. Michael Lewis, in his wonderful book Premonition: A Pandemic Story, will tell you, as would Dr. Charity Dean. Dr. Dean was featured in Lewis’s book, and she was invited to be on this panel, but she emailed back a message saying that she was overloaded with work and couldn't make it. If you read Michael Lewis's book, you will see a failure in public health, documented. And if you read Niall Ferguson's book, you will see the meat of history and lessons we can learn from it.

Here we are, confronting history today. It's up to us, and we're not doing well. The challenge is global. Long haul symptoms are global. Deaths are global. So we need to be very careful, because there's a lot at risk at hand. I'll close with a slide from Colorado Springs. It speaks for itself. Thank you very much.

(Photo taken by David Kotok in the museum at the Garden of the Gods Nature Center near Colorado Springs)

David R. Kotok

Chairman of the Board & Chief Investment Officer

Email | Bio

Links to other websites or electronic media controlled or offered by Third-Parties (non-affiliates of Cumberland Advisors) are provided only as a reference and courtesy to our users. Cumberland Advisors has no control over such websites, does not recommend or endorse any opinions, ideas, products, information, or content of such sites, and makes no warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, reliability or suitability of their content. Cumberland Advisors hereby disclaims liability for any information, materials, products or services posted or offered at any of the Third-Party websites. The Third-Party may have a privacy and/or security policy different from that of Cumberland Advisors. Therefore, please refer to the specific privacy and security policies of the Third-Party when accessing their websites.

Cumberland Advisors Market Commentaries offer insights and analysis on upcoming, important economic issues that potentially impact global financial markets. Our team shares their thinking on global economic developments, market news and other factors that often influence investment opportunities and strategies.